Glossopharyngeal Neuralgia

This information is designed only to help patients talk with their physicians about Glossopharyngeal Neuralgia (GPN) and is not intended to provide treatment guidelines.

Introduction

Glossopharyngeal neuralgia is a very rare neurologic condition that causes intermittent, extremely painful, one-sided throat pain. It is exactly analogous to the much more common trigeminal neuralgia (where the pain is in the face) but the affected nerve is the glossopharyngeal instead of the trigeminal. Each glossopharyngeal nerve (there is one on the right and one of the left) is responsible for sensation in the back of the tongue and throat. That is why the pain is felt in the back of the tongue and throat. The pain is triggered by touching this area – i.e. by swallowing.

By 2015, we have seen well over a 1,000 patients with trigeminal neuralgia but only 14 with glossopharyngeal neuralgia. It is truly rare – a hundred times less common as trigeminal neuralgia.

The type of pain is identical to trigeminal neuralgia – “electrical bolts of lightning going down the back of my tongue” or “like swallowing shards of glass“. Only the location is different – it occurs in the throat not face. The pain is typically brief and lasts only a few seconds but the attacks can be multiple. Patients can mistakenly report that their pain is constant but it is really repeated bouts of intermittent pain. This is a very important distinction. I have seen two patients with truly constant pain in the throat that turned out to be a neuropathic deafferentation pain not GPN.

Rarely (less than half the time) patients with glossopharyngeal neuralgia get symptoms also related to the Vagus nerve. The Vagus nerve (cranial nerve X) is located immediately beside the glossopharyngeal and can be compressed by the same blood vessel. When the Vagus nerve is involved, patients can feel pain deep in their ear. Strong Vagus nerve involvement can cause profound slowing of the heart rate – these patients get episodes where they feel their throat pain and then suddenly lose consciousness (faint) because their heart stops for a moment! This unusual condition is sometimes called vago-glossopharyngeal neuralgia.

Patients with glossopharyngeal neuralgia can also sometimes (10%) have associated coughing and very rarely can also have choking episodes. Our team was the first to highlight this association in a recent peer-reviewed paper (see paper #2 in our publications).

We believe glossopharyngeal neuralgia occurs when the nerve losses its insulation (myelin). This most typically occurs when a blood vessel rubs against the nerve for many years. This blood vessel is typically the posterior inferior cerebellar artery or PICA. We believe the blood vessel wears away the insulation of the nerve and allows the nerve to ‘short-circuit’. Normally, touching the throat triggers a nerve impulse in a branch of the Vagus and that information travels down the ‘touch’ branch of the nerve to the brain and signals the throat has been touched. In Glossopharyngeal neuralgia, that nerve branch has lost its insulation and therefore the normal touch signal can ‘short-circuit’ into another branch of the nerve which normally carries pain signals. The swallowing therefore triggers a very painful sensation in the throat. Over the years, the condition will typically fluctuate with symptoms going away for several months (remission) and then returning again (relapse). The natural history of this condition is slow worsening – remissions get shorter and relapses get more severe over the years.

There are at least four other potential causes for the loss of myelin around the glossopharyngeal nerve.

The first is Eagle’s syndrome. This is a rare condition, known to most ENT specialists, where the nerve is caught against an abnormally long piece of bone sticking down from the bottom of the skull. The nerve rubs against the bone and is demyelinated causing glossopharyngeal neuralgia. This condition is diagnosed by a CT scan of the skull which shows the styloid bone is longer than 3 cm. The treatment is an ENT procedure to brake off that piece of bone.

The second is a tumor in the neck near the pathway of the glossopharyngeal nerve. This can be diagnosed with a CT scan using contrast dye. The treatment is directed towards treating the tumor/cancer by an ENT specialist.

The third is multiple sclerosis where the patient’s own immune system attacks the myelin. The loss of myelin may be inside the brain along the ‘pain pathway’ from the nerve to the trigeminal caudalis nucleus. This must be exceedingly rare – I have treated over 300 patients with multiple sclerosis and trigeminal neuralgia but can not remember one with GPN.

The fourth is a viral infection of the nerve. This usually causes demyelination resulting in the touch-induced electrical pain but ALSO causes nerve damage which can cause a sensation of constant pain (often burning) in the same area of the throat. This condition is extremely difficult to treat and usually requires a pain specialist. Long bouts of burning after a series of electric shock-like pain is common but constant burning 24/7 suggests a different diagnosis – glossopharyngeal neuropathic pain rather than glossopharyngeal neuralgia.

Medical Treatment

Just like trigeminal neuralgia, glossopharyngeal neuralgia can be treated with medications. The medications and rational are the same – anti-epileptic medications are used to try and stop the nerve from ‘short circuiting’. Patients can try a variety of medications under the supervision of their neurologist. There are many different medications that can be effective (e.g. carbamazepine (trade name: Tegretol), neurontin (Gabapentin), pregabalin (Lyrica)).

In general, if the medications can control your symptoms, there is no need for surgery. If the medications can not control your pain OR if the side effects of the medications are intolerable (e.g. sedation) then you are a potential candidate for surgery.

If the throat is numb, it usually can not trigger glossopharyngeal neuralgia. In the old days, ENT specialists used to confirm the diagnosis by putting a pledget soaked in cocaine in the back of the throat. This numbed the throat and typically blocked the glossopharyngeal neuralgia for the length of the anesthetic effect. The addictive properties of cocaine stopped the practice and now specialists use a local anesthetic such as Marcaine. Patients should discuss with their specialist if a topical anesthetic mouth wash could help them. As with every medication, caution is required and too much anesthetic can adversely affect the heart.

Surgical Treatment

The benefits and risks of surgery must be discussed directly with your neurosurgeon. The risks can vary between centres with different experience.

Just like trigeminal neuralgia, a microvascular decompression of the glossopharyngeal nerve will work in the vast majority of cases. Not all patients will be cured by the perfectly performed operation because the surgery just decompresses the nerve (by moving the blood vessel away) it does not remyelinate the nerve. We rely on the body to heal and remyelinate the nerve – which it can do in the vast majority of cases. Sometimes, however, the nerve is too badly damaged to heal and the pain continues. Unfortunately, there is often very little room around the nerve to push the vessel away from the nerve. Because the nerve and the vessel (held away from the nerve with a Teflon padding) often remain in close proximity, recurrent compression with recurrent painful symptoms is a problem with this operation. Some surgeons (including our team) recommend cutting the glossopharyngeal nerve instead of decompressing it. This reduces the chance of recurrence and is well tolerated by the patient.

When the upper fibres of the Vagus nerve are involved, the situation becomes more complex. Ideally, the surgery in those cases would also include cutting the upper sensory branches of the Vagal nerve. This was first recommended by the Stockholm team in 1962. Cutting any of the motor branches of the vagal nerve will cause difficulty swallowing and a hoarse voice. In order to avoid the motor branches of the vagal nerve, we have published our recommended method of special intraoperative monitoring (see paper #45 in our publications). Each rootlet of the Vagus nerve (there are typically 5 or 6) is tested to see if it causes a contraction of the throat before it is cut. We would recommend only cutting those branches which do not cause a throat contraction (i.e. spare all motor branches of the Vagus nerve). Our interest in glossopharyngeal neuralgia has provided new information on the neuroanatomy and physiology of the glossopharyngeal and Vagus nerves. We have recently published this work in peer-reviewed medical journals for the benefit of our colleagues (see paper #9 in our publications).

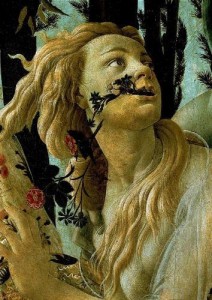

The picture below is a close-up from Sandro Botticelli’s “Spring” (Primavera) from the late 1470s. Chloris is being transformed into Flora (spring) and we see the side of her neck. This is the location of glossopharyngeal neuralgia which radiates down one side of the throat, much like the vine extending down her neck.